US 12 and the Burr Trail

Lynne and I had to make another visit to a clinic this morning since we were both physically deteriorating and worse than we were when we went to the first clinic. Although we immediately felt better after our first clinic visit, that changed day by day. The doctor told us that our initial medication may have suppressed our immune system leading to our current bacterial infection or masked it for a while. She told me that I have junky lungs but she doesn’t think I have pneumonia. We have a new set of medications to hopefully fix us before our flight home.

We took our meds and embarked on the most anticipated part of the trip, traveling U.S. Highway 12 (Scenic Byway 12) considered one of the most spectacular drives in the United States. The road runs about 123 miles (198 km) across southern Utah, connecting US-89 near Panguitch to UT-24 near Torrey, linking Bryce Canyon National Park and Capitol Reef National Park.

Along the way, the highway passes through a remarkable range of landscapes and public lands. What makes this road special is the dramatic change in landscapes over a relatively short distance. In a single drive you may pass through:

- red-rock deserts and hoodoos

- slickrock canyons and slot canyons

- alpine forests and aspen groves

- high mountain plateaus

- historic ranching and pioneer communities

Because of this diversity, the route is often called “A Journey Through Time Scenic Byway,” revealing more than 200 million years of geologic and human history along the route. It is also a designated All-American Road which is the highest designation in the U.S. National Scenic Byways Program, administered by the Federal Highway Administration. It is considered one of the most remarkable drives in the nation.

To qualify, a road must:

- Have multiple exceptional qualities (scenic, natural, historic, cultural, archaeological, or recreational).

- Offer features so unique they can’t be found elsewhere in the country.

- Be a destination in itself, not just a route to somewhere else.

We turned off US 12 in Boulder to follow the Burr Trail through Long Canyon, a scenic backcountry route that winds from the edge of the Aquarius Plateau down through towering red-rock walls before crossing the Waterpocket Fold in Capitol Reef National Park and continuing toward Bullfrog on Lake Powell. The road begins as pavement in Boulder, climbing gently through sagebrush flats before entering Long Canyon, where sheer sandstone cliffs rise hundreds of feet above the road and massive fallen boulders create one of the most dramatic passages along the route. After going through Long Canyon, we only drove a few more miles before returning and saw sweeping views of the canyon country which we found nearly impossible to photograph because of the breadth of the landscape.

On the return trip, we stopped in Escalante and grabbed a bite to eat at a place that was an outfitter, a state liquor store, and a restaurant all in one. It was lovely.

Scenic Drive to Rainbow Point and Kodachrome State Park

Past the amphitheater in Bryce National Park is an 18 mile drive atop part of the Paunsaugunt Plateau. We headed for the point in hopes of walking the Bristlecone Trail where we hoped to see bristlecone pines, wildlife and fantastic views. As we entered the park, there was a light dusting of snow. The top of the plateau is 7,000 to 9,100 feet in elevation and there was more snow the higher we went. We arrived at our destination and the trail was snow covered with 27 degrees temperature and blowing wind. We did not have the gear for this, so we limited ourselves to taking photos from the observation points and froze doing it.

Later in the day, we visited Kodachrome Basin State Park. It is a colorful park about 20 miles southeast of Bryce Canyon National Park. It’s known for its red, orange, and cream-colored sandstone “chimneys” (sedimentary spires), with more than 60 rising from the basin floor. The park was named in 1949 by a National Geographic expedition who felt the vivid colors were worthy of Kodachrome film. The colors are most spectacular at sunrise and sunset and we were there mid-afternoon.

Arriving at Bryce Canyon National Park

When we left Springdale this morning, we were gifted to see a group of mule deer as we exited the parking lot from our lodge. It was a great way to start the day.

On our trip to Bryce Canyon, we saw a bird of prey sitting on a pole. I stopped and Lynne got the image. It’s a red-tailed hawk.

We arrived too early to check into our lodge, so we went straight to the park and embarked upon a 3 mile hike. There was ice, slush, and water on parts of the trail and we found the last section was closed so we had to turn-around and go back the way we came. We wound up walking almost 5 miles. Being that we aren’t the healthiest right now, it was difficult toward the end.

Once we got in the lodge, we elected to chill for the rest of the day and make plans for our remaining days here. The area is spectacular and there are many choices. As I often say, there are no bad choices.

Mule Deer, Best Friends Animal Sanctuary

Feeling better, Lynne and I headed east through Zion National Park early in the morning to look for wildlife. Our goal was to visit Coral Pink Sands State Park and then visit Best Friends Animal Sanctuary. We got good views of the morning sun lighting up some of the peaks in the park.

We were successful several times in seeing mule deer. Our first look was a group of about 15. We saw several more groups of mule deer throughout the morning. We also saw juvenile bald eagles, one adult, many ravens and a variety of other birds.

Our stop at the Coral Pink Sands State Park was at a bad time to take good pictures but it was beautiful and we enjoyed the birding.

Then, we headed to Best Friends Animal Sanctuary located in Kanab, Utah which is the largest no-kill animal sanctuary in the United States. On its thousands of acres, the Sanctuary provides a safe, healing home for up to 1,600 animals — including dogs, cats, horses, pigs, birds, rabbits and more — many of whom arrive needing medical care, rehabilitation, or simply a second chance at life. Operated by the nonprofit Best Friends Animal Society, it serves as both a refuge for animals who may never find permanent homes and a hub for adoption, volunteering, education, and tours that help further the organization’s mission of ending the killing of homeless pets nationwide.

Lynne and I visited Angel’s Rest which is a cemetery for pets who have crossed the rainbow bridge. Pets are either buried there or there are chimes hanging to memorialize a pet. It is one of the most touching places on the planet. I have been there before and tried to resist breaking down by focusing on the bird life, which was amazing. Lynne was sniffling so I thought it might be from whatever we came down with, but not so. Soon after, I lost it. I was wise enough to bring a box of tissue. It was quiet and peaceful.

While there, I saw ravens building a nest and a Woodhouse scrub jay.

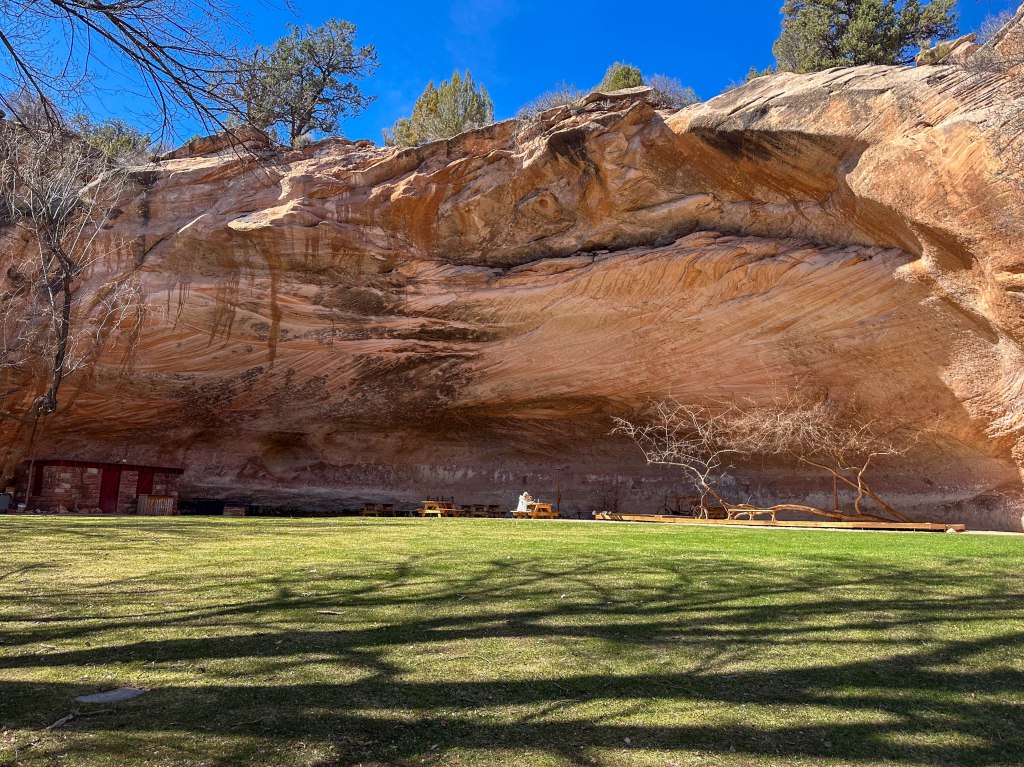

Later, we went to the natural amphitheater and ate our lunch. While there, we heard what sounded like an enormous number of bees buzzing. I roamed around and found that the trees were just beginning to bud out and there were bees visiting the blossoms. The sound of all those bees visiting trees near the amphitheater resonated against the rock and was amazing.

On our way back through the park, the traffic was crazy. It was a warm Sunday and there was a lot of cars and people. We got back to the room and chilled.

Utah Excursion

My friend Lynne and I headed to Utah on a 10 day excursion. We flew on Breeze Airways from Jacksonville to Las Vegas because they were the only direct flight. The flight got off to a late start exiting the jetway and then we sat on the tarmac because there were allegedly F22’s doing touch and gos. We waited and never saw them. Eventually, the invisible F22’s finished their touch and go’s and we were off. One and half hours out from Las Vegas, the flight attendant announced the toilets were full and could not be used. I have never had that happen before. Lynne and I were concerned during landing they might spill over.

After waiting eons to get the bags, we had to figure out how to get to the car. When I asked directions on my cell phone, it said it was 1 hour and 58 minutes away walking. That did not sound good. We managed to find the shuttle and go to the other end of town to get our Jeep Rubicon. It probably took 20 minutes to get it going. There was no user manual in the car and I couldn’t figure out how to stop it from being upset about the back seats where some of our gear was located. We relocated ALL the gear to the very back and was able to get the car started and exit the garage.

We arrived safely at our room in Springdale just as the sun was setting. The next day, we drove through Zion National Park to scope it out. We had plans to hike up Angel’s Landing even if we couldn’t make it to the top. During regular season, you can’t drive through the canyon. You must take the shuttle. The season starts March 7 so we were able to drive. We stopped at the Visitor Center on the way out and found that there was ice on the trail to Angel’s Landing and spikes were suggested. We both have them but left them at home. Also, there is a lottery to get to the top. The icy conditions nixed our plans. It is hard enough to do this without ice.

Since we nixed the Angel Landing hike, we chose to do the hike to the Emerald Pools the next day. Following is a video:

It’s 3 miles round trip and we were particularly beat at the end. We took the afternoon off and enjoyed the local rock squirrels and other wildlife.

I felt increasingly bad as the day wore on and realized I had a fever. I looked for a local clinic of which there is no such thing. I found something in a town 25 miles away that was open on Saturday. Lynne was also feeling poorly. We went to bed super early and our health did not improve during the night. We headed to the clinic in time for it to open and it turns out it was open from 8-7, not 7-8. We sat around in the parking lot and picked up at least one life bird while waiting.

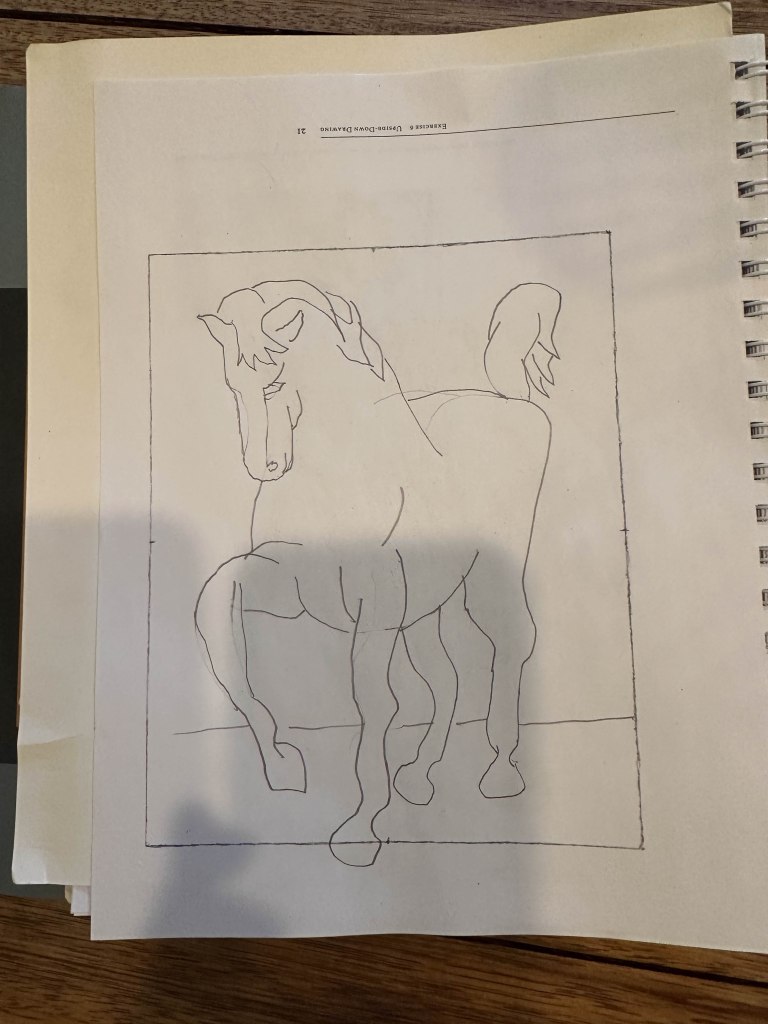

We were the first ones in and got taken care of with prescriptions to improve our situation. We stopped at Walgreens to pick them up and swallowed the first dose in the parking lot. By the time we got back to the lodge, we already felt better. The excursion was saved!! We lazed around all afternoon and I started to read a book on how to draw and it suggests drawing upside down. Here is one of my free hand drawings done upside down. I’m pretty excited that I may be able to improve on my non-existent drawing skills.

Florida Photo Fest and More Whales

I will be offering several classes and workshops at the upcoming Florida Photo Fest in St. Augustine April April 23-26. Registration opens February 16. Classes include: Birding Hot Spots Near Florida and Using Photography to Support Conservation. Workshops include: Photographing Sunset on a Coquina Beach, Bird Identification and Photography Birds Near Water at Fort Mose Historic State Park, Bird Identification and Photographing Birds Near Water at the GTM, and Photography 101: A Beginner’s Guide to DSLR and Mirrorless Photography.

Yesterday was another amazing day watching a mother and calf pair of northern right whales accompanied by dolphins off the northeast coast of Florida. Following is some video. Around the 44 second mark, look for the dolphin in the lower right.

Travel Trailer

I miss having an RV. Although I love going out on the boat, I’m usually good for no more than two weeks and the dogs can’t come on the boat. When I was in Washington, I had a small RV which we camped in a few times. Enough to know it was going to be rough as the collies grew bigger. There was not a lot of floor space. Dart was still alive and not tolerant of the collies once we stopped and set up camp. When I decided to move back to Florida, I consigned the RV and sold the tow vehicle so I wouldn’t have to figure out how to get two cars, an RV, and two puppies across country. If it had been a more ideal camping solution with two big dogs, I think I would have figured it out.

My wonderful real estate agent, Maureen Nightingale, once asked me what I would do if I could do what I wanted. I told her I would live in Florida most of the year and spend the summers in Washington State. If I had the means, I would have kept the house in Washington so I could do that. I have regularly looked at renting something, but it’s expensive. I often thought of getting an RV, but I need something small and affordable that will work with two big dogs. I did not think a solution was out there.

I recently put together some albums from some of our RV trips and I included information from our blogs and my favorite pictures. Going down memory lane got me antsy. About two weeks ago, I went to the nearest RV dealer (Blue Compass) to see the options. When I described the truck I had and the need to have space for the dogs, the sales rep took me to see a Jayco Jay Feather travel trailer that did not have a kitchen table. It has open floor space when the slide is out and can be hauled by our truck. It was perfect. (Good sales guy (Merec) who listened to what I said.) I cranked through our finances and got Regis to double-check the numbers and tried to figure out if I could get it. There are some things I have to give up, but worth it to me. I bought it.

I have never driven with a regular trailer. We had a fifth-wheel for our first RV and I drove it sometimes, but Regis was the one who got it into and out of the campgrounds. A fifth-wheel is easier to handle than a travel trailer. I am determined. The thing is, Regis is not interested in camping anymore, so this is going to be solo with two dogs. He will help me out until I can handle it on my own, but this has to be something I can do by myself.

Because the day I was supposed to pick up the trailer I had another commitment, Regis chose to pick it up rather than reschedule. He got home shortly after me and backed the rig into the driveway. As I watched him, I was scared. When it was on the dealer lot, it looked small compared to all the other RV’s. Now that it was in the driveway, I wondered how I was going to haul it.

We took a couple days to look it over and load basic stuff and today I drove it to the storage lot. It took more time for me to back up the last 20 feet than it took to get from the house to the storage lot. Oh my goodness do I need some practice. We found a nearby parking lot for me to practice. In the meantime, I booked campsites for most of August and September on the Olympic Peninsula. The dogs are going to love me for this. Summers are so hot in Florida that I can’t walk them in the heat. We are going to walk our butts off in Washington.

Upcoming Eco Tours Boat Trip

I have been working with St. Augustine Eco Tours to provide boat trips along the Matanzas and Tolomato Rivers for photography and bird watching. Captain Zach Mckenna is a wildlife researcher and naturalist with two decades of experience on our waterways. I am a Florida Master Naturalist and I am particularly knowledgeable about the birds. We have two boats scheduled for February 20 and 22 starting at 8:30 am to look for the birds who winter along the Tolomato River. Following are links to two Tolomato Boat Trips. These are two hour trips with a limit of 10 participants to allow room for photography gear. The cost is $65 per person. The boat will leave the St. Augustine Municipal Marina and take 1/2 hour to get near the airport and mouth of the Guana River to see the birds that winter here. There are usually large numbers of white pelicans at this time of year and plenty of oystercatchers. The boat will hang out for an hour and then take 1/2 hour to get back. The winter visitors will start migrating back soon, so this is the best chance for a good Tolomato River trip until next fall.

Last week I got to spend some time photographing northern right whale Ghost and her newborn calf. At the end of the video, there is a boat. They are trying to get a DNA sample of the calf. I’ve been having trouble with WordPress lately and my current problem is an inability to embed the whale video. The best I am currently able to do is give you the ugly link below and let you know it is currently the most recent video on that link.

I recently completed a felting of my friend’s dog Bella.

Right Whales

I participate in the right whale survey that takes place from the beginning of January to mid-March. I have been doing this for most of the last 9 years. Ground teams from Ponte Vedra to Ponce Inlet in Florida look for whales every day. This season, 15 right whales were spotted before the official season started and that was more than all the whales seen last year. The official ground surveys started last Tuesday and whales were seen the first 3 days. I was co-guiding a boat tour on Thursday and got the notification of a whale as I got off the boat. One of my boat mates went with me to see the mother/calf pair and we were not disappointed. The water was calm and lovely.

The North Atlantic right whale (Eubalaena glacialis) is one of the most endangered large whale species in the world, with fewer than 400 individuals remaining. They earned the name “right whale” because they were once considered the right whale to hunt—slow-moving, rich in blubber, and likely to float when killed. Today, their greatest threats are no longer whaling but ship strikes and entanglement in fishing gear, which continue to limit population recovery.

Each winter, pregnant females migrate from northern feeding grounds off New England and Canada to the calving grounds off the coasts of northeastern Florida and southeastern Georgia. These waters are relatively shallow, calm, and warmer—conditions that are safer for newborn calves that lack thick blubber and strong swimming ability. Calves are typically born between December and early March, and mothers remain in the region for several weeks while nursing and building the calf’s strength before beginning the long journey north. She seldom eats during this time because there is insufficient food available to her.

Because this region is so critical to the species’ survival, intensive survey programs operate from January through mid-March. Planes fly the coastline and nearshore waters to locate right whales, document mother–calf pairs, and photograph individuals for identification based on their unique callosity patterns. Ground teams search for whales from the shore. When spotted, drones or planes are brought in to identify the whales. When whales are sighted, their locations are rapidly shared with federal agencies, mariners, ports, and shipping interests so that vessel speed restrictions and routing advisories can be implemented to reduce the risk of collisions.

These seasonal surveys, combined with public awareness and compliance with slow-speed zones, play a vital role in protecting right whales during their most vulnerable life stage. Northeastern Florida and Georgia are not just winter destinations—they are essential nurseries whose protection directly influences whether this species can recover and persist into the future.

Momma right whales show only a small portion of their body as they lie in the water. They can be hard to spot. They do not jump up in the air like humpbacks or orcas. The baby whale may frolic in the water and expose its tail or flippers. Sometimes the momma whale will turn expose her large flippers. But, there is no dramatic whale display. There is just a momma right whale taking care of her newborn while it frolics and grows big enough to go back north in more food productive but colder waters.

Right whales are identified by unique features called callosities. Callosities are rough, raised patches of thickened skin found on the heads of North Atlantic right whales. They begin forming before birth and develop primarily on the rostrum (upper jaw), around the blowholes, above the eyes, and along the lips and chin. The callosities themselves are dark gray or black, but they often appear white, cream, or yellowish because they are colonized by tiny whale lice (cyamids), which live only on whales and do not harm them.

What makes callosities especially important is that their size, shape, and arrangement are unique to each individual whale, much like a human fingerprint. The overall pattern remains stable throughout a whale’s life, even as the whale grows. Because of this consistency, researchers use high-resolution photographs—often taken during aerial surveys—to identify individual whales, track mother–calf pairs, document movements, and build long-term life histories.

Callosity patterns are a cornerstone of right whale conservation science. By allowing scientists to recognize individuals without tagging or disturbing them, callosities make it possible to monitor survival, reproduction, and injuries over decades. This noninvasive identification method is one of the key tools used to understand population trends and to guide protections for this critically endangered species.

Glass and Dogs

Tonight, I managed to break a glass container while washing it. I can break glass or crystal faster than anyone on the planet. It was in the sink while I was cleaning it, but the glass pieces wound up on the floor. Regis hurt his arm fixing my tire a couple of weeks ago and cannot walk both dogs at the same time. I took the dogs for a walk while he cleaned up the glass. This leads to an amazing ability I have. I can attract a bicyclist whenever I walk both dogs at the same time. If one of the dog poops and I stoop down to get it, 100% of the time, a bicyclist will come by. Raven could have a firecracker shoot off next to his head and he wouldn’t flinch, but a bicyclist makes him apoplectic. For reasons I cannot understand, EVERY time I walk both dogs by myself and one poops, a bicyclist will come by while I am cleaning up. 100% of the time.

Merry Christmas to everyone.